Books dealing with various aspects of queer spirituality seem to be becoming more popular at the moment, so for my first book review for the new year I thought I’d take a look at two books that use the title “Queer Magic”. Both titles are the Kindle editions.

First up is Tomás Prower’s Queer Magic: LGBT+ Spirituality and Culture from Around The World (Llewellyn Publications 2018). This approach to “Queer Magic” takes the form of a global expedition into the ‘hidden’ queer history of world religious cultures. Divided into seven sections, each focusing on particular regions, their cultural traditions, and some exploration of “queer deities, legendary figures, and mythic lore. There’s also a selected reading list for each chapter and each section closes with guest contributions from contemporary LGBT+ practitioners. This book very much reads like a personal journey, as the author says, “all the information I wish someone had given me when I began my quest” and that it is intended to be “your passport to worlds you never knew existed, populated by people and spiritual beings just like you, regardless of who you are.” As far as I can make out, ‘Queer’ in the sense that Prower uses it, is very much an umbrella term for LGBT+ identities.

First up is Tomás Prower’s Queer Magic: LGBT+ Spirituality and Culture from Around The World (Llewellyn Publications 2018). This approach to “Queer Magic” takes the form of a global expedition into the ‘hidden’ queer history of world religious cultures. Divided into seven sections, each focusing on particular regions, their cultural traditions, and some exploration of “queer deities, legendary figures, and mythic lore. There’s also a selected reading list for each chapter and each section closes with guest contributions from contemporary LGBT+ practitioners. This book very much reads like a personal journey, as the author says, “all the information I wish someone had given me when I began my quest” and that it is intended to be “your passport to worlds you never knew existed, populated by people and spiritual beings just like you, regardless of who you are.” As far as I can make out, ‘Queer’ in the sense that Prower uses it, is very much an umbrella term for LGBT+ identities.

The first Part of the book opens the “Cradles of Civilisation” – Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt, to Judaism and Islam, which nods the reader in the direction of queer Sufi mystics and the controversy of how ‘queer’ Rumi may have been. The section closes with contributions from a contemporary devotee of the deities of ancient Mesopotamia, Dr Jacob Tupper; from Rev. Tamara L. Siuda, founder of the Kemetic Orthodox Religion; Keren Petito on growing up queer and Jewish and Saifuddin Mohammed, a gay Muslim from India.

Part Two of the book covers Sub-Saharan Africa and the lands of the African Diaspora – which may be a surprise for some readers, as Prower points out that many modern African states are openly hostile to queer communities. The two chapters in this section cover Eastern & Southern Africa, Western & Central Africa, the lands of the African Diaspora – with a focus on Vodou, Santería and Candomblé. The section closes with contributions from Sandra Zuri, a queer Yoruban practitioner, and the Rev. Tamara L. Siuda – who is also an initiated Vodou practitioner.

Part three of the Book examines Europe and begins with a look at sexual identities in Ancient Greece and Rome, and from then on into “Pagan Europe” with a look at the Celts, the Scandinavians, and following up with a chapter on Christianity. The section closes with a contribution on homoerotic love spells from Antinoan P. Sufenas Virius Lupus; Druid and Drag Queen Kristoffer Hughes; and Leah Gonzales on being a Blatina bisexual in the Catholic Church.

Part Four moves to the Indian Subcontinent, with chapters on Hinduism and Buddhism. I’m biased here, due to my own interests, but I thought these chapters were rather weak. Yes, trying to approach the complexities of contemporary LGBT+ politics in India is a huge subject, as is identifying potential queer elements in its diverse religious traditions, but uncritically repeating assertions such as that Ganesha’s trunk “is often seen as a phallic symbol” or that “The major cultural shift of Hindus condemning queerness as a social evil largely came about in the 1920s, 30s and 40s spearheaded by, of all people, Mohandas Gandhi” comes across to me, I’m afraid, as sheer laziness – particularly given the controversial nature of both statements. The section on the Indian Subcontinent ends with a Puja Ritual for “inner divine queerness” by Ganapati Kamesh of the Oklamoha-based Shri Ganapatikamesh Matha, and a contribution by Nikko, a gay Nichiren Buddhist.

Part five covers East Asia, with chapters examining China (Taoism and Confucianism and Mahayana Buddhism) and Japan (Shinto and Japanese Buddhism) and Shamanism. The section ends with Prower’s own reflections on Taoist thought and practice, and Nikko giving an example of a Nichiren Buddhist Mantra.

Part Six deals with Oceania, beginning with Aboriginal Australia, moving on to Polynesian Islands and the Maori, Samoa, the Tonga, Tahiti, and Hawai’i. In the absence of any direct contributions from Oceanic practitioners, Prower recommends the documentary film Kumu Hina – which won the GLAAD media award for outstanding documentary in 2016.

The seventh and final section of the book covers the Americas, beginning with Latin America and then moving to Native North America and, unsurprisingly, a discussion of the term “two-spirit” and its politics. The section closes with a Santa Muerte Protection spell from Anthony Lucero and a Southwestern Sage ritual from Brian Simpson, a gay Native American of the Dine/Navajo tribe.

The author also gives some space to “takeaway” summaries for how queer readers can implement a tradition’s wisdom into their own lives and spellwork – although he cautions, in his introduction, that “I highly discourage you from immediately and arbitrarily incorporating these cultures and deities into your own personal practice just because of capricious curiosity. Eclectic spirituality and cosmopolitanism are one thing, but appropriation and lack of cultural reverence are another. Many of these queer traditions and deities from around the world will call to you and speak to you on some intrinsic level, but do personal research before jumping into foreign waters.” That’s as close as we get to any discussion of cultural appropriation or similar issues.

It’s this emphasis on “personal research” which I feel, is the main strength of this approach to “Queer Magic”. The book offers an introduction to the examination of queer elements in different cultural, religious, and magical traditions. Prower makes it very clear that this is a starting point only, and not an attempt to be one of those “only books you’ll ever need”. Yet at the same time – in trying to cover the entire globe, and say something meaningful about cultures both contemporary and premodern, I cannot help but feel he has tried to pack too much into too little space.

Also, a problem with a book like this is that citing sources is all very well and laudable, but when those sources are outdated, or repeat ‘facts’ which are controversial, if not just plain “dodgy”, then that becomes all too clear, very quickly. Also, Prower tends to zoom into the realm of speculation. For example, in a discussion the Buddha’s attractiveness, he speculates that “one could argue that he directly marketed himself to the gay community in order to spread his message” – one could argue this, I suppose, but it rather begs the question of how far Nepal, in the 6th-4th century B.C. had much of a “gay community” in the sense we think of it nowadays. This tendency – all too common to queer spiritual writing – to slip into an easy equivalence between contemporary (Western) LGBT+ identities and those of other cultures and epochs runs throughout “Queer Magic” although the author does point out the differences, and that in some respects, modern readers might find aspects of premodern cultures – such as Greek pederasty – repugnant.

Sometimes, “Queer Magic” does come across as being over-reliant on dated textual sources, although the contributions from the various contemporary practitioners is a nice offset to this, and lifts the book away from being just another ethnocartographic work attempting to universalise western ideas of subjectivity. Having said that, there are also some interesting omissions – for example, almost nothing is said about contemporary Pagan traditions and their relationship with LGBT+ history.

In general though, Queer Magic is definitely worth a look, if only for the contributions of the contemporary practitioners.

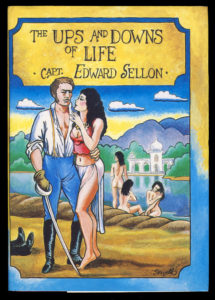

The second book is Queer Magic: Power Beyond Boundaries edited by Lee Harrington and Tai Fenix Kulystin (Mystic Productions Press 2018). Power Beyond Boundaries is an anthology of contributions from forty-three contemporary practitioners and activists, many of whom are based in North America. The contents and approaches are highly diverse, including personal reflections, rituals, interviews, poetry, artwork and cartoons. I’m not going to examine each contribution in turn – which would take far too long, but instead will focus on some broad themes and highlights.

The second book is Queer Magic: Power Beyond Boundaries edited by Lee Harrington and Tai Fenix Kulystin (Mystic Productions Press 2018). Power Beyond Boundaries is an anthology of contributions from forty-three contemporary practitioners and activists, many of whom are based in North America. The contents and approaches are highly diverse, including personal reflections, rituals, interviews, poetry, artwork and cartoons. I’m not going to examine each contribution in turn – which would take far too long, but instead will focus on some broad themes and highlights.

Several of the contributions deal with what we might think of as queer approaches to Wicca, Witchcraft, and neo-pagan practice. These include Yvonne Aburrow’s “Inclusive Wicca Manifesto”; Giariel Foxwood’s thought-provoking essay on what happens when the terms “Witchery” and “Queer” are brought together; Steve Kenson’s “Queer Journey of the Wheel”; Sam ‘Eyrie’ Ward’s “The Maypole and the Labyrinth: Reimagining the Great Rite”; and Ivo Dominguez Jr.’s “Redefining and Repurposing Polarity” which rethinks the concept of polarity beyond gender binary or opposites. There are also personal reflections on alchemy – one by occasional contributor to this blog Steve Dee, Almah LaVon Rice’s moving “Between Starshine and Clay: DIY Black Queer Divination” and Alex Batagi’s experience of Vodou. There is magic to support justice workers, queer ancestors, rites of rage, power, and healing.

There are some fascinating and moving interviews, featuring for example, Clyde Hall, Shoshone Two-Spirit Elder and one of the founders of the Gay American Indian Caucus in which he shares some insights into the modern construction of “Two-Spirit” as an identity.

One of the outstanding essays for me, is Aaron Oberon’s “A Drag Queen Possessed and other Queer Club Magic”; a joyous celebration of queer performativity which emphasizes “practice within the immediacy of the witch’s environment” – where “certain kinds of magic-such as glamour, protection, lust, and even possession-might be more potent in a queer night club than in other places throughout your landscape.”

Another outstanding piece is Abby Helasdottir’s “Umsnúa: Ergi and inversion in Old Norse magical practice”. An in-depth, scholarly essay on the Icelandic witch Ljót the Old Norse ergi with its multiple layers of abjection, and manages to cite Judith Butler, Carolyn Dinshaw and Kenneth Grant. Susan Harper, Ph.D gives a heartfelt reflection on her long involvement in Feminist Goddess Spirituality and directly addresses issues such as class privilege, race, the “appropriation” of Native American and African practices, symbols and deities, and the exclusionary practices. “Many of us never realized” she says “who “womyn born womyn” was leaving out. Harper, in her essay, makes an important distinction between inclusionory practices – inviting people into spaces which have already been created, and affirming practices – where the emphasis is on the co-creation of social spaces. She goes on to look at how transphobic or trans exclusionary practices/rhetoric can exist within spaces which are otherwise well-meaning, particularly in spaces where the gender binary is taken as the template for human relationships. She goes on to discuss a series of Best Practices for Creating and Facilitating Affirming Spaces which I think would be of great value to group and workshop facilitators.

Although I was initially wary of the American slant of Power Beyond Boundaries the sheer breadth and diversity of its contents and communicative styles make it easily one of best books on queer magic I’ve come across, and, I would say, sets a high benchmark for future projects. Having a wide range of contributors not only in terms of traditions but also of age and ethnicity gives the book a strong intersectional and historical perspective, and what also comes across is a clear commitment to queer activism and resistance.

It would be unfair to compare these two books with one another – although both are titled “Queer Magic” they are coming from very different perspectives and assumptions as to what Queer Magic’s entailments and potentials might mean, and so serve different purposes. The key difference, I think, is how you see queer subjectivity – as an identity which has always existed and can be recognised or refracted through cultures and epochs, or as a product of modernity and something that points beyond identities and desires. Perhaps there’s room for a bit of both.

Interview with some of the contributors to Power without Boundaries